June 21, 2023

Throughout the 2023 Chicago mayoral campaign, Mayor Johnson stated that it was his intention to avoid increasing property taxes, citing concerns about the burden already placed on many Chicagoans. But, while the impact of property tax increases on individual homeowners and business owners is an important factor to consider, the new mayoral administration must also weigh the property tax in context of the City’s overall revenue needs and its competitiveness compared to other parts of the region. The property tax should not be ruled out completely. However, decisions about whether to increase the Chicago property tax levy each year should be reviewed and approved by City Council as part of the annual budget process, and should never be assumed automatically.

Pros and Cons of Property Tax as a Revenue Source

There are several arguments in favor of the City’s reliance on the property tax as a significant source of revenue. Property taxes represent the single largest revenue source for the City of Chicago annually. It is considered a stable and reliable revenue source to most governments as it does not fluctuate significantly with economic cycles like other sources such as income and sales taxes. The property tax levy can also be raised through the City’s own home rule authority, without requiring approval from any other government bodies outside of City Council, though it does have a self-imposed property tax cap.

However, property tax increases tend to be unpopular with the general public because it is a very visible tax, paid only twice a year in two large sums and is not directly linked to a taxpayer’s ability to pay. Additionally, there are many governments that are allowed to tax property in Chicago and they do not work in concert when making their property tax plans. If property taxes are raised significantly in a single year, they can impose strains on property owners, especially those with fixed incomes. For more information about how the Cook County property tax system conforms to fundamental principles of taxation, please read this primer. The Civic Federation’s comprehensive position on the Cook County Property Tax System is available here.

Background on City of Chicago Property Taxes

Property taxes are the City’s largest revenue source. They are estimated to generate $1.7 billion in revenue in FY2023, representing approximately 20% of the resources supporting the City’s Corporate Fund, library, debt service and pension funds. When accounting for all of the City’s non-capital and non-grant funds, referred to as all local funds, property tax represents about 13% of total local funds revenue.

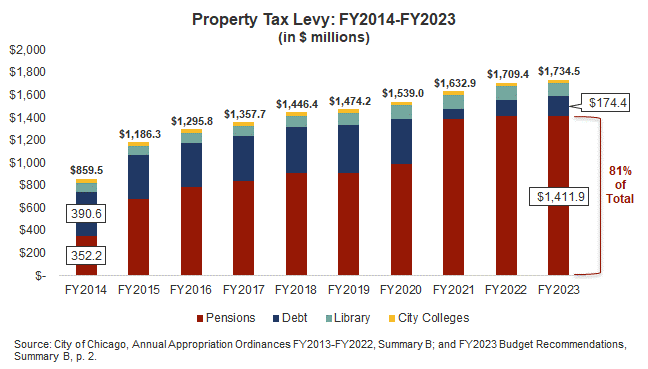

The City of Chicago’s property tax levy is used for four purposes: 1) payments to the City’s four pension funds; 2) debt service funding (a portion of this is transferred to Chicago Public Schools per an intergovernmental agreement); 3) debt service payments for Chicago Public Library bonds; and 4) General Obligation Bonds to pay for City Colleges of Chicago capital projects. Property tax revenue is not used for general operating purposes within the Corporate Fund. The majority of property tax revenue, 81%, is used to fund pensions.

Historically, property tax increases were generally avoided in Chicago. The property tax levy held steady at approximately $700 million for about a decade between 1999 and 2007, before increasing to $800 million, where the levy remained for the next several years. In 2015 Mayor Rahm Emanuel and the City Council instituted a significant property tax increase to address the City’s pension funding crisis. The increase was passed by the City Council as an amendment to the FY2015 property tax levy as part of the FY2016 budget adopted in October 2015 in order to pay for increases in statutorily required pension contributions to the Police and Fire pension funds. The 2015 amendment increased the City’s property tax levy from $831.5 million in FY2015 to $1.4 billion in FY2018, representing a 70% increase phased in over the four-year period.

Mayor Lightfoot’s administration instituted a practice of raising the property tax levy used to pay for pension contributions annually by the rate of inflation. However, inflationary increases became untenable when the inflation rate increased significantly in 2022. Rather than increasing the levy by the maximum 5% allowed based on this policy, the City instead increased the levy for FY2023 by 2.5%.

Over the past ten years, the property tax levy has increased by $875.0 million, or 102%, since FY2014. The amount of property tax revenue allocated to pensions as a portion of the total levy has grown significantly, while debt service as a portion of the levy has decreased. This is due in part to savings from refinancing bonds issued by the City and the Sales Tax Securitization Corporation.

It should be noted that there are ways the City can generate additional property tax revenue each year in addition to a general increase. The City can levy for the expiring tax increment financing (TIF) increment and levy for new property. Governments in Illinois are allowed to increase their revenue beyond what normally would be allowed under the tax cap law by applying their tax rate to the increased value of property in expiring TIF districts and by applying the tax rate to new or improved (redeveloped) property. The City of Chicago as a home rule municipality is not bound by state-imposed tax caps, but is still able to take advantage of levying for these additional revenues. Taxing expiring TIF increment does not effectively raise an owner’s property taxes; rather, the amount of their tax bill that would have previously been paid into the TIF subsequently goes to the government levying for the expired increment. And a levy on new property only affects taxpayers with new or improved property, so therefore is also not considered to be a general property tax increase. Both of these are methods of raising property tax revenue that the City has used fairly often

As a home rule unit of government exempt from state legal limits on property tax increases, the City has the authority to increase its property tax levy without any limits. However, the City has a self-imposed property tax limit that mirrors the state Property Tax Extension Limitation Law, which limits the annual increase in the aggregate property tax extension to the lesser of 5% or the rate of inflation. The aggregate property tax extension is the levy of property taxes for all purposes, but excluding amounts levied for special service areas, pensions and the library. The 2015 increases to support contributions to the Police and Fire pension funds were not exceptions to the City’s self-imposed limit because extensions for pensions are not included in the aggregate levy.

The City later in FY2021 added a provision to the property tax levy used to pay for pensions, tying the levy to the annual rate of inflation or 5%, whichever is less. In the current high inflationary environment, an annual property tax based on the rate of inflation results in hitting the cap of 5%. The Civic Federation’s position on this policy is that all property tax increases should be reviewed based on need in context of the entire City budget, and approved by City Council annually, rather than being tied to an automatic inflator.

In addition to the property tax levy, the City also receives and distributes property tax revenue for tax increment financing (TIF) districts within Chicago boundaries. The tax revenue generated in a TIF district is not appropriated as part of the City budget and is not levied for by the City.

Considerations for Raising Property Taxes

Key considerations for city leaders when weighing an increase to the property tax levy are: how much capacity do property taxpayers have to pay more tax and would an increase make the City’s property tax rate uncompetitive compared to surrounding communities? Because of its large commercial and industrial tax base, Chicago has relatively low tax rates compared to surrounding municipalities. However, it will be important for the City to not overburden the tax capacity of residents and business owners.

Chicago's Property Tax Capacity

The City’s levy is only a portion of the entire property tax bill that residents and businesses pay. The Mayor and City Council must consider the City of Chicago’s property tax levy in context of the entire tax burden on property owners. In tax year 2021 (payable in 2022), the City of Chicago received 23.3% of an average property tax bill. The majority, 52.5%, went to Chicago Public Schools. Another 6.4% went to the Chicago Library Fund, City Colleges and the City of Chicago School Building and Improvement Fund. The remaining portions go to the other overlapping taxing districts, including Cook County, the Cook County Forest Preserve District, the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District and the Chicago Park District.

As noted above, compared to suburban communities, the City of Chicago composite tax rate, which means the combined rate for all of the taxing bodies that overlap City borders, is relatively low due to the large commercial and industrial property base. The tax year 2021 composite tax rate in the City of Chicago was 6.7%, which is lower than the average composite tax rates in the suburbs (the lowest of which is an average composite rate of 7.2% in Burr Ridge).

Tax rates are calculated based on the dollar amount of governments’ levies divided by the equalized assessed value (the amount of taxable property) of all property within the jurisdiction. As the value of property grows, it is important for the City of Chicago to think about increases to its property tax levy in the context of the levies of other overlapping governments because an increase by any Chicago-based local government puts more burden on all property owners.

Chicago’s Effective Tax Rate in Comparison to Other Illinois Municipalities

Another important factor in determining the City’s capacity to raise property taxes is the effective tax rate. The effective tax rate is a function of the assessed value of property that makes up the tax base. It represents an average calculation of the percentage of property’s value that is actually paid in taxes and allows for comparisons of tax burdens to be made across jurisdictions. When the value of a government’s tax base increases, it gives a government the capacity to generate larger amounts of revenue through the property tax without raising rates since there is more value to tax.

The City should look at whether a property tax increase would make effective tax rates uncompetitive relative to other communities in the region.

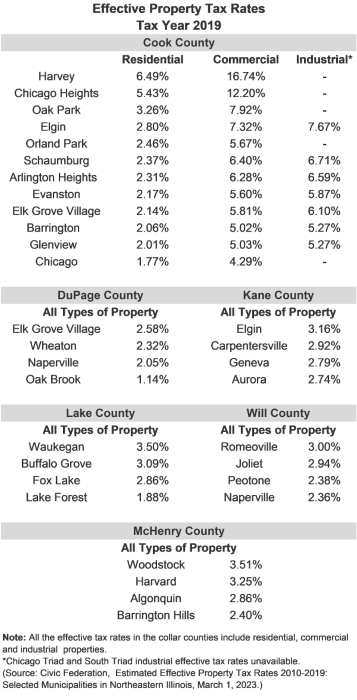

Despite the City of Chicago’s increases in property taxes over the past decade, Chicago’s effective residential property tax rate is still lower than most surrounding suburbs in Cook County and many of the collar counties, at 1.77% as of 2019. Chicago also had lower commercial effective tax rates at 3.61% than any of the other selected communities in Cook County. The commercial effective rate was higher than most of the selected collar county rates due to the fact that Cook County classifies property differently than other counties. The effective property tax rates of selected municipalities in the Chicago region are shown in the following table.

From a comparative perspective, the City of Chicago appears to have the capacity to increase property taxes on residential properties and not lose its competitive edge in effective tax rates. It has less room for increases to effective tax rates for commercial properties.

Impact on Property Owners

As an ad valorem tax, the property tax is based on property value and not directly related to income. So while an increase in a homeowner or business owner’s assessed property value is an increase in wealth, it does not necessarily mean a taxpayer has more income to use to pay taxes. If a homeowner’s income grows at a slower rate than their property tax bill or they experience economic hardship, they may need eventually to sell their home and move to a lower value residence or a different jurisdiction with lower tax levels. If a homeowner’s effective tax rate is flat in a growing real estate market, while the percentage of the home’s value they pay in tax is flat, the total amount of tax paid has gone up.

There are homeowner’s and senior citizens’ property tax exemptions in Cook County enabled by State statute starting in 2017 as an attempt to offset some of the impact of increasing property taxes by reducing the taxable value of residences. But since the Cook County property tax system is a zero-sum game, any reduction in tax liability to residences means other types of property, including apartments and commercial and industrial property, have to make up the difference.

In addition to residents, City leaders will need to think about how property tax increases impact the business climate, especially given the continuing downtown recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, and forecasts of a potential recession.